China Focus 1: Wally Rhines maps startup and design growth

Semicon China begins in a month (March 20-22). It had more than 90,000 attendees in 2018 and filled the cavernous Shanghai New International Exhibition Centre. It illustrates the levels of activity in the Middle Kingdom’s electronic systems market, and how they are driven by the state’s ambitious goals for its Made in China 2025 program – and alongside that its aggressive bid to become the world leader in artificial intelligence by 2030.

How are things going? China is seen as a tough read. But combining key metrics and looking at them next to global design trends, can provide solid insights into how the sector is evolving and the challenges that remain.

In the time between now and the start of Semicon China, we will review analyses of China’s performance recently presented by key figures and organizations, local and global. And we’ll offer a few observations of our own.

We start with one of those global observers. Wally Rhines is President and CEO Emeritus of Mentor, a Siemens business. As head of one of the ‘Big 3’ EDA vendors, he is necessarily a keen analyst of overarching trends in silicon design. Speaking last year in Seoul, Rhines considered the current global growth drivers in semiconductor design and particularly highlighted their Chinese components.

There are two broad trends. Chinese companies have access to – and are getting – venture capital (VC) funding. They are consequently not only growing in number but also size. This is allowing them to take on more complex projects. Beyond that, there are the influences of AI and the types of design it now requires.

Funded in China for 2025

“One reason for the [global] acceleration in chip design has been the injection of funding by the Chinese government. In 2014, the Chinese government announced a $20B fund which was channeled though private equity and matched by nearly another $100B to create a fund to promote IC manufacturing as well as development and design,” Rhines said.”

“While most of this went to manufacturing, increasingly funding is being made available for design. In a newly-rumored $47B fund, it’s expected that design will play an even greater role in adding to the creativity of the Chinese semiconductor industry.”

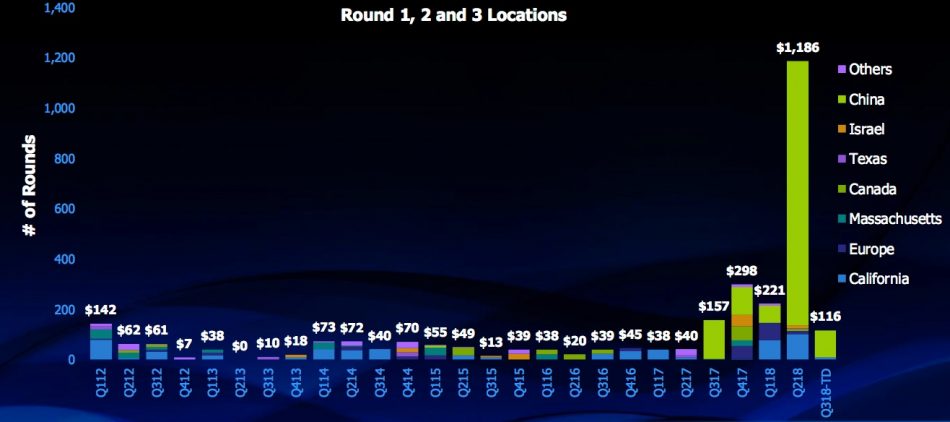

But already, Rhines noted, when it comes to AI-aimed processors “most of the money is from the Chinese funds.” Their spending is greater than that targeting Silicon Valley (Figure 1). “And one Chinese company is accounting for about half of the total, SenseTime.”

Figure 1. Early round Chinese fabless funding passes US levels (GSA/VentureSource/Pitchbook/Mentor – click to enlarge)

SenseTime received a $1B investment from Shanghai-based SoftBank China Venture Capital last Summer. SoftBank is the investment fund driven by Japan’s Masayoshi Son and is the owner of ARM. It is looking to pour $100B into various cutting-edge technology investments worldwide.

But SoftBank is just one heavy hitter. China has a good few more, led by the BAT trio of Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent.

China skills up

With all this money available – and with Hong Kong and Shanghai evolving into technology investment centers equivalent to New York and San Francisco – Chinese startups are mushrooming in number.

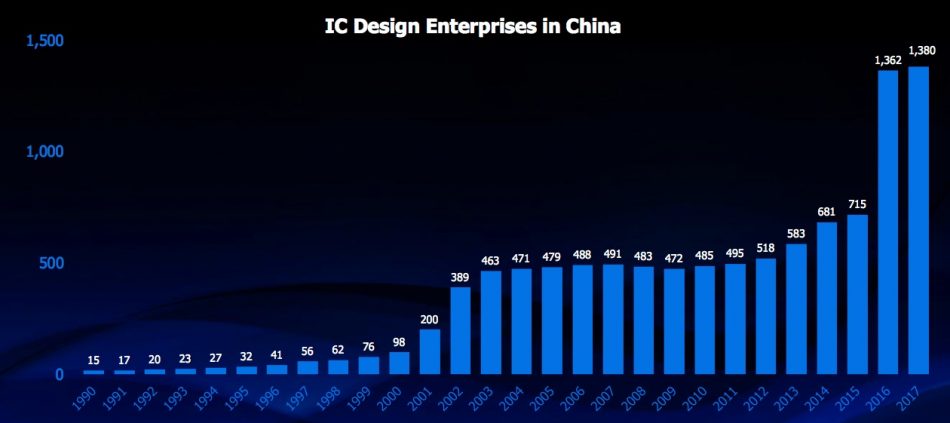

“The number of fabless semiconductor companies in China grew to around 500 through most of the last 15 years,” Rhines told his audience. “But now, at least as reported by China, that number has accelerated to near 1,400 fabless semiconductor companies.”

Figure 2. China’s semiconductor initiatives have accelerated startup numbers (Mentor/TrendForce/PwC – click to enlarge)

There was a feeling not that long ago that Chinese startup numbers were that indicative of real activity. The stereotype was of a company comprising three people in one cubicle: an application specialist, an engineer and a salesperson.

There may have been some truth there, given local and national government investment in incubators, and the perception of how ‘maker’ culture has been nurtured in big tech cities like Shenzhen. Think of a plethora of Palo Alto garages with Chinese characteristics. But some of these flowers are beginning to bloom.

“If you look at those Chinese fabless semiconductor companies, you find that they are growing to be much larger,” Rhines said.

“For example, in 2006, the percentage of the reported fabless semiconductor companies in China that had 100-500 employees was about 10%. In 2015, that number had grown to almost 44% of the total number of fabless semiconductor companies. Similarly, for the number between 50 and 100, that too has grown.

“So, the companies are becoming bigger and able to do more design than in the past.”

Domain-specific architectures

The end targets for Chinese designs are shifting. This reflects the greater money and resources companies have, and the needs of their customers.

“If you look at the type of design these Chinese fabless companies are doing, increasingly they are moving away from what was mostly power devices and analog,” Rhines said. “Now, an increasing number are doing more sophisticated digital processing and domain-specific processors for video, vision processing and artificial intelligence.”

China watchers point to multiple drivers behind this.

First, there is the New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan, unveiled in 2017. Beijing has set progressive goals that China should match the US in AI by 2020, achieve world-class performance in some segments by 2025, and be the overall world leader by 2030.

Second there is the role of the BATs (or for silicon design this is often recast as ‘BATHs’ to note the influence of Huawei and its Hisilicon subsidiary). A map of the Chinese silicon design market connects most leading startups to one of these companies, either as a client or a strategic investor. All four have also been assigned government priorities under the AI plan (these are covered later in this series).

Third, there is this concept of ‘domain-specific’ processors. Rhines cited its use in a recent speech by John Hennessy, chair of Google parent Alphabet.

“There is a major wave occurring in design today to develop what are called domain-specific architectures for chips that are very good at doing a small set of things compared to general purpose microprocessors….

“[Hennessy] gave a talk at the DARPA electronics research initiative a few weeks ago and highlighted the fact that in order to continue to improve the performance, power and cost of semiconductor products, we need to develop domain-specific architectures that can do just a few tasks but do them extremely well.”

Domain-specific processors are largely a response to the demands of AI. As data volumes increase the processing load and algorithms are refined, one of the questions in AI silicon is whether the currently standard GPU- and FPGA-based architectures are running out of steam. Some companies are going down an application-specific route, but others believe that multi-use processors (even if less general than GPU or FPGA) represent a more economically viable way forward because AI is evolving so rapidly at the system level.

SenseTime, recipient of that huge SoftBank investment, is a case in point. It is best known for its facial recognition technology, but today presents itself as much as a platform/ecosystem vendor enabling customers to develop their own systems.

EDA for big and small

All of this is good news for an EDA vendor like Mentor. It certainly allows Rhines to push back against those who wonder how semiconductor design will carry on growing in the longer term.

But with regard to the immediate challenges, Rhines sees design automation now enabling companies big and small – and, indeed, Chinese or otherwise – to take on advanced challenges such as those presented by AI. There is an alignment across these factors and EDA’s evolving capabilities and reach.

“Many of the domain-specific processors are focused on computer vision or neural computing, high bandwidth cellular or image processing and video compression. It’s necessary for these companies to be able to develop these chips in much less time with better results to be able to prototype in a field programmable gate array or retarget to custom silicon, and to be able to manage late changing specifications and reduce the verification debug cost and time,” he said.

“We have said recently that small companies can’t design complex chips because it’s too complex, takes too long and costs too much money. But in fact the change in design methodology has made it possible for many small companies to develop their own domain-specific processors.”

Here Rhines sees a particularly big opportunity for high-level synthesis (though Mentor is also getting traction in AI for its emulation products).

“[HLS] takes the design description to a higher level. Data from Qualcomm shows the relative amount of time required to handcode Verilog or VHDL versus doing it in HLS with a language like C or C++. On average, it’s a 75% reduction in the time required to achieve equivalent results or better,” he said.

“So the designer creates the design for the datapath – the compute intensive part of the design – in C++, and then synthesizes it so you can target and FPGA or other custom design. The reason that they are able to achieve better results than with hand-coded is because they can try so many different alternatives to see which has the lowest power and the highest performance.”

Tools for the job. Companies you can sell them to. A burgeoning Chinese market. And plenty of technology goals to be met (indeed, the Trump administration is now looking to develop its own answer to China’s AI program). Rhines feels Mentor is in a good place. Indeed, further analysis leads him to suggest that growth across the worldwide semiconductor industry is unlikely to peak until 2038 – but we’ll come back to that later.