China Focus 2: The Design Dilemma

This is part of a series of weekly articles looking at current challenges facing Chinese system design in the run up to March’s Semicon China conference and exhibition.

Part One of China Focus looked at funding going into local system design, the growth in active companies and the potential influence of domain-specific architectures. Part Two looks at dynamics influencing Chinese design trends and how they could be fueling tension over the direction China’s strategy is taking. Much of that is coming down to how leading players are interpreting ‘domain-specific’.

The country’s ambitious goals for artificial intelligence (AI) illustrate the issues. AI spreads across other national technology priorities such as Beijing’s programs in semiconductor manufacturing and design, autonomous driving, e-health and smart cities.

But we also need to look at China’s technological evolution before AI climbed the agenda. That process helped to spawn the megacompany BAT triumvirate of Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent, and continue Huawei’s growth. However some of its strengths may need to be rethought as the country seeks to move from ‘follow-and-run’ to world leader..

How the flowers bloomed

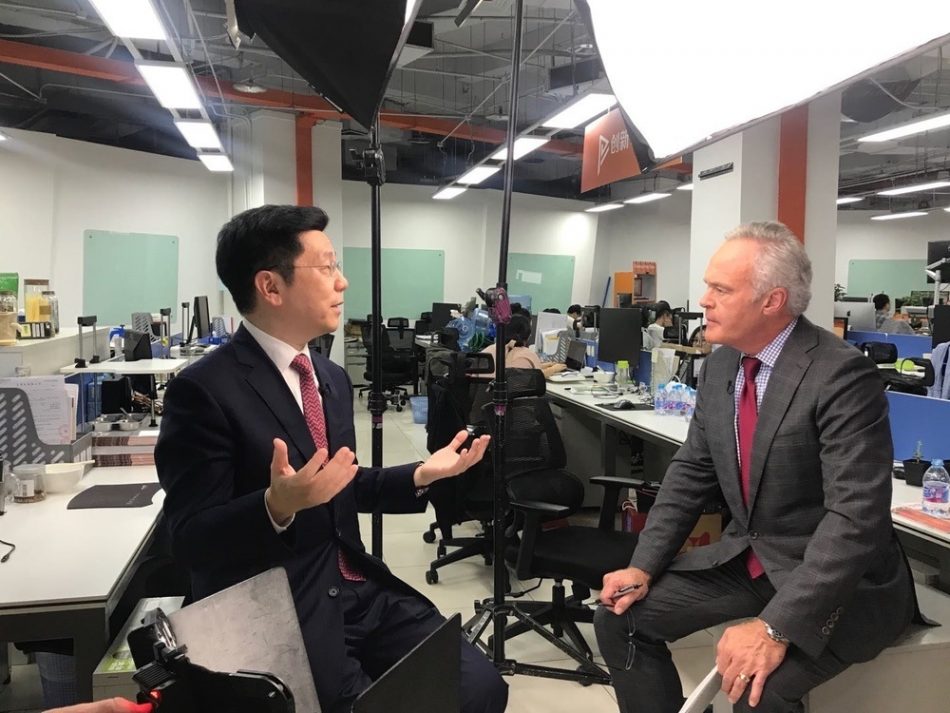

Kai-Fu Lee is a Chinese technology rockstar. He leads one of the country’s leading venture capital firms, Sinovation Ventures. Before that, Lee was a pioneering researcher in speech recognition, established Microsoft Research Asia and ran Google China from 2005-2009.

Lee’s latest book, AI Superpowers: China, Silicon Valley, and the New World Order, contains fascinating technological and philosophical ideas about how AI is set to evolve. But more important, it outlines how China’s Internet economy originally developed.

Lee acknowledges that copycatting was an important factor, but he adds other nuances and observations. Here are four that are specifically relevant.

The first is that copies were not “stumbling blocks” destined to confine their developers to eternal me-too status. Rather they were “building blocks” – they were “a necessary steppingstone on the way to more original and locally tailored products.”

The second is that China today has a plethora of “gladiatorial” and “world-class” entrepreneurs promoted by government policy and exhortation. They are willing to chance their arms in new industries, get close to their markets and, as we saw in Part One, can now more readily secure investment.

The third is that China has to date rewarded strategies that go “heavy” rather than “light”.

In the light version, “Silicon Valley startups will build the information platform but then let brick-and-mortar businesses hand the on-the-ground logistics.”

The heavy version practiced by many successful Chinese startups is one Lee broadly characterizes as O2O – online-to-offline. “They don’t just want to build the platform – they want to recruit each seller, handle the goods, run the delivery team, supply the scooters, repair those scooters, and control the payment. And if need be, they’ll subsidize that entire process to speed user adoption and undercut rivals,” Lee writes.

“To Chinese startups, the deeper they get into the nitty-gritty – and often very expensive – details, the harder it will be for a copycat competitor to mimic the business model and undercut them on price.”

The fourth is that while all this was happening – and, indeed, as Chinese government regulation placed obstacles before foreign investors – few US companies sought to understand the nuances of the Chinese market anyway. Most still don’t: “They’ll make limited efforts at localization but will largely stick to the traditional playbook. They will build one global product and push it out on billions of different users…. It’s an all-or-nothing approach with a huge potential upside if the conquest succeeds, but it also has a high chance of leaving empty-handed.”

This model goes a long way toward explaining the success the BATs and others have achieved, particularly if you then add the Chinese people’s far greater comfort in living online. One recent study there found that the country’s volume of mobile payments over services like Alipay and WeChat exceeds that of the US by a ratio of 50:1.

But there is some concern now that – Harvard Business School cliché alert – some of these sources of success may be holding China back today, as the copying stops and innovation becomes a national priority.

China and the application-specific trap

China is a command economy. The technology goals in and around the Made in China 2025 plan are clear, including its for world leadership across AI by 2030, as set out in 2017’s allied New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan.

It includes elements that have a deep, market-specific focus.

The government has nominated four of its existing world-class companies to head AI R&D in core target markets: Baidu in autonomous driving; Alibaba in smart cities; Tencent in medical vision; and iFlyTek in voice intelligence.

There is also a lot resting on – and expected from – the work being done by other established companies and the latest unicorns. These include Da-Jaing Innovations (DJI) in drones, SenseTime in computer vision and deep learning, Face++ in facial recognition, Cambricon in edge and cloud computing silicon, and Horizon Robotics for AI, embedded vision and advanced automation chips.

And, of course, there is Huawei.

There have already been some impressive ‘wins’. One example is Huawei’s Kirin AI chip. In another, Baidu has unveiled a minibus based on its Apollo autonomous driving framework. DJI’s founders, Zexiang Li and Frank Wang, received last year’s prestigious IEEE Robotics and Automation Technical Field Award. Meanwhile, SenseTime raised more funding than just about any other silicon design company in the last year – more than $1.6bn.

So why are there undercurrents of concern?

Jeffrey Ding is a specialist in Chinese AI trends at Oxford University’s Future of Humanities Insitute (he also publishes an invaluable an email list on the topic, including exclusive translations of Chinese speeches and papers). In a recent MIT Technology Review report, he observes, “I haven’t really seen much out of China with regards to fundamental breakthroughs that set a new frontier.”

In the same paper, SenseTime co-founder Wang Xiaogang, offers this overview. “There are two levels in AI research. One is the foundation level; the other is the application level. You will see in China a lot of AI companies focused on the application level, scenarios in different industry or process domains.”

If China has issues with the balance between fundamental and applied research, it is hardly alone. But there is the feeling that they may have been exacerbated at least in part by the earlier drivers Lee identifies.

In particular, there is the emphasis current entrepreneurs have learned to put on building out the application/product to scale.

The Sword and the Qi

Get not just big, but very big fast. Supply chain first, ecosystem second… if at all. Or alternatively, can we put this in the model of the domain-specific architectures discussed earlier by Mentor’s Wally Rhines and Alphabet’s John Hennessy? In a recent post for the Chinese science and technology website Huxiu, staff writer Qian Dehu* seems to argue somewhat along those lines.

Taking an analogy from Chinese literature, he divides the country’s leading AI companies into two factions, the ‘Sword’ and the ‘Qi’.

The Sword faction looks for quick results that can be directly applied to its core businesses and applications. These can still be complex challenges in machine learning or vision. But the design priorities continue to be defined by the O2O approach.

The Qi faction takes a long term view, looking at those technologies that reach down to the fundamental level.

According to the original work, the Sword wins, but as the years pass the Qi becomes the more powerful. “Internal strength is first learned and then the sword-style is learned, so that a sword can be sharpened before mistakenly chopping the firewood,” he says.

Qian Dehu offers another analogy that locates the three BATs specifically, based on their current research priorities.

“Consider making bread,” he writes. “Baidu [a Qi company] will research how to make bread, it will become the best wheat grower, flour processor and bread baker; additionally, in this process, it will form strategic alliances with seed traders, fertilizer companies, builders and retailers.

“Then under this scenario, Alibaba and Tencent [Sword companies] are more eager to buy the finished bread products that suit their tastes, and quickly improve their e-commerce efficiency and social efficiency, and then further consider how to empower other companies in the same business areas.”

So, there is evidence of a pivot, and that will be the focus of Part Three. But before we go there, as with all things China, we need to look at where the government may be itself shifting on the Sword/Qi split.

We can get some evidence from a recent speech to a standing committee of China’s governing National People’s Congress by Tan Tieniu, a professor in computer vision and pattern recognition and Deputy Secretary-General of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. It was full of encouragement, but did not shy away from highlighting perceived shortfalls in research.

“There is still a relatively large gap between the level of the world’s leader and China’s level in basic research, novel achievements, top talent, technology ecosystems, foundational platforms, and standards and specifications. A 2018 research report by the University of Oxford in the UK pointed out that China’s AI development capabilities are roughly half those of the United States. At present, China’s frontier theoretical innovations in AI are still in the ‘follow-and-run’ stage. Most of the innovations are biased toward technical applications, and a ‘top-heavy’ imbalance results.”*

He then went on to observe: “In addition, China’s AI open source community and technology ecosystem are relatively lagging behind, the establishment of technical platforms needs to be strengthened, and international influence needs to be improved. China’s participation in the development of international standards for AI is not sufficient, and the formulation and implementation of domestic standards are lagging behind. The process of formulating and perfecting laws and regulations related to AI in China needs to be accelerated, and there is still a lack of in-depth analysis of possible social impacts.”

So how do you address this? Is Baidu a model for future Chinese design priorities? What about another success story, China’s approach to 5G? Are there others? And what about investor pressure, given that the proposed pivot might be seen as deviating from a successful template?

The third part of this series looks at how 5G has provided a research, development and business template that China is looking to use elsewhere within the Made in China 2025 framework – though it may not transplant all that easily from one domain to another.

* This article is indebted to Jeffrey Ding and his colleague Cameron Hickert, of Harvard’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, for their translations of Qian Dehu’s article and Tan Tieniu’s speech (you can find their original translations in full at the two links here, where you will also find links to the originals in Mandarin).