Mentor’s Wally Rhines on M&A ‘merger mania’

Were the current rate of mergers and acquisitions (M&A) in silicon to continue growing unchecked until 2020, the industry would by then have rationalized itself into a single company. So notes Mentor Graphics chairman and CEO Wally Rhines in a keynote that he’s been delivering at a number of events across Europe and Asia.

Of course, that isn’t going to happen. But these are interesting times. By early August, this year had already seen 19 mega-deals with values of more than $50m. Among them were NXP Semiconductors’ buy of Freescale Semiconductor, and Intel’s purchase of Altera. Things have carried on with the more recent announcement that Dialog Semiconductor is to acquire Atmel for $4.6bn.

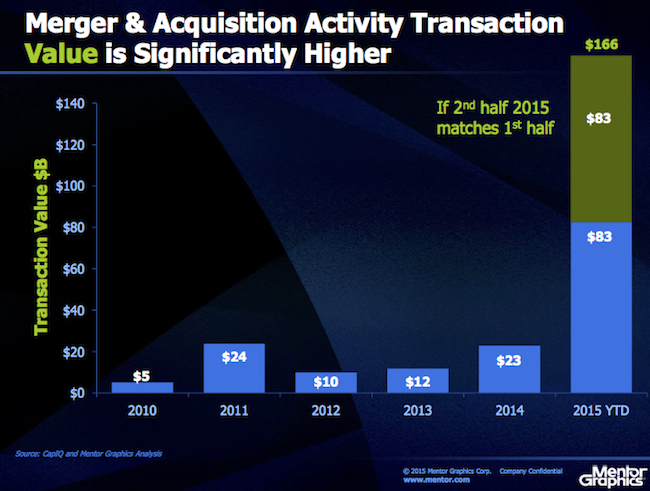

M&A is picking up speed. 2014 saw 32 big transactions. This followed 16 in 2013 and 18 in 2012. But the real contrast is found in transaction values. These have rocketed from $23bn in 2014 to $83bn in the first half of this year.

What’s going on? Rhines breaks down the core of his analysis into three areas: two significant but one arguably less so here than generally assumed:

- Economies of scale

- Financial leverage (liquidity)

- Regulation/government mandate

Just how low (or high) can you go?

Received wisdom suggests that when you merge two huge companies, there should be huge economies of scale. But once you get beyond levels of duplicated management, administration and sales, Rhines pointed out that the opportunities are often overstated.

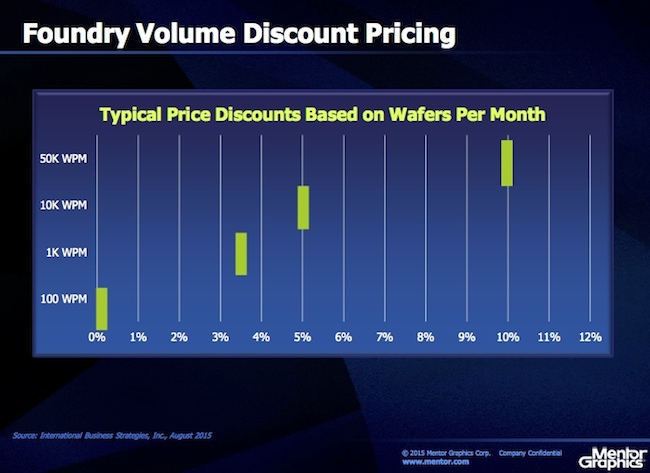

Consider manufacturing. The factory was often at the heart of rationalization. But few semiconductor companies own factories or even make the majority of their own chips anymore. They use foundries that offer aggressive, competitive pricing and discounts. That price-model holds especially true for the higher volume products where the greatest scale economies traditionally lie. Foundries can therefore offer cost-effective manufacturing to the whole market.

Of course, you can reverse this and rather than looking at where you can be lean, look at the extra people you can throw at a problem. But here, Rhines noted, you might quickly fall pray to Brooks Law: “Adding manpower to a late software project makes it later.”

Rhines asked the audience to consider that within a 10-person design team, there are potentially 2^10 connections and person-to-person relationships: 1,024. Double the team to 20 and you are now managing 2^20 connections: 1,048,576.

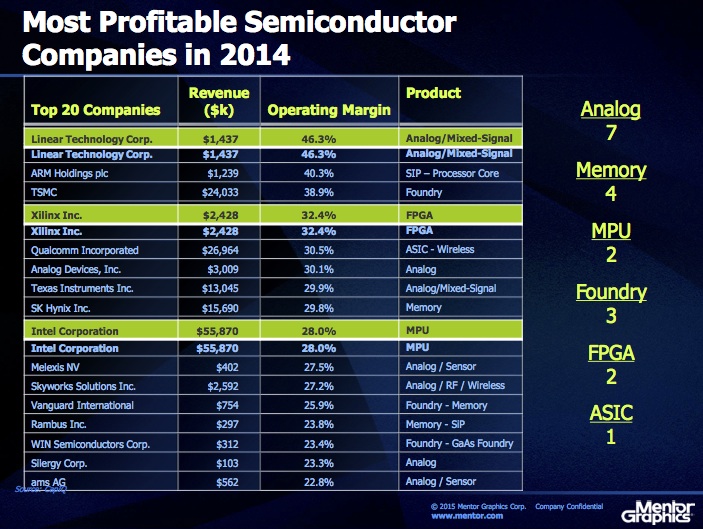

Perhaps most telling is Rhines’ ranking of the most profitable chip companies not by their revenues, but operating margins. In this view, Linear Technology, the analog and mixed signal specialist, is first with a margin of 46.3% on 2014 sales of $1.4bn. FPGA company Xilinx is fourth (32.4% on $2.4bn sales) and Intel is ninth (28.0% on sales of $55.9bn).

In a modern business environment, economies of scale alone are harder to fine, and within an IP-driven sector like semiconductors, other factors can determine your overall profitability.

Easy M&A money

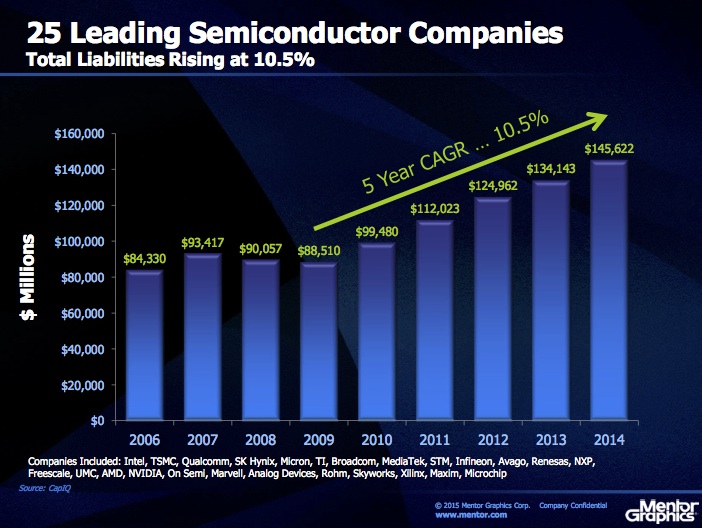

In the aftermath of the recent financial crisis, cash is available at extremely low interest rates. Liquidity is high and the leading semiconductor companies are taking advantage, Rhines showed. After a period of falling or remaining flat, cash/short-term investments at the 25 biggest players are showing CAGR of 8.1%, while liabilities among the same firms are rising at a CAGR of 10.5%.

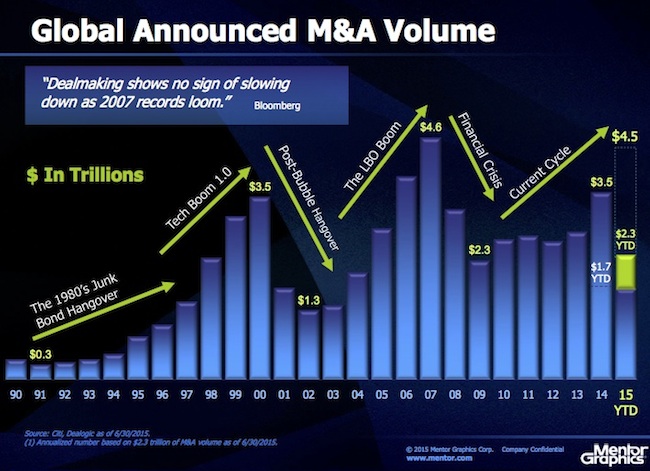

All this is following an established cycle in M&A that Rhines portrayed dating back over a quarter-century. We’ve been here before. It is a good time to do deals, and most of those going through appear to make business sense in terms of combining or adding new technologies/competences to an enterprise. But it won’t last. It never does.

M&a-ke it so

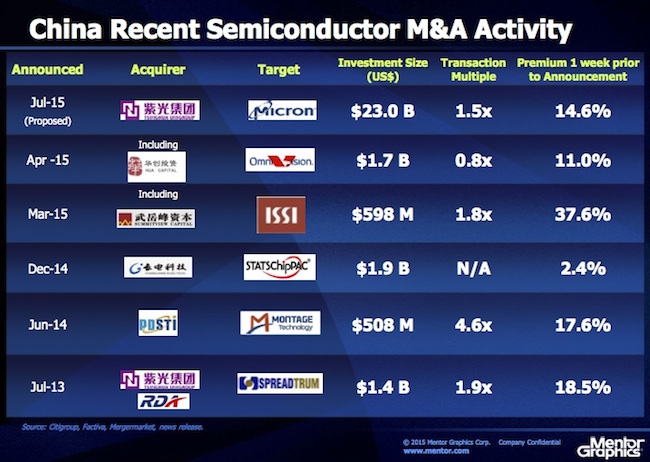

Rhines cited six major M&A deals involving Chinese buyers since July 2013. He also quoted one of the country’s online media outlets from earlier this year: “China announced its five-year plan to expand its semiconductor industry by over 20% annually by investing $20bn in both domestic markets and acquisitions in foreign countries.”

At the time of writing, Tsinghua Unicom’s unsolicited $23bn approach to memory expert Micron Technology still has hurdles to cross (in recent days, there have been claims that the deal may be unraveling). However, the scale of the bid remains a statement of intent even if this particular marriage is not consummated.

Where major companies flag an interest in being acquired and/or have a technology that China particularly aims to master, either a local private equity player or state-owned enterprise may well enter the fray. The two sectors are increasingly encouraged by Beijing to work jointly on M&A deals.

China is not the only such player. Arab sovereign wealth funds continue to review electronics and semiconductors as one path to economic diversification, as they prepare for a world after ‘peak oil’. Meanwhile, the research funds directed through transnational bodies such as the European Union can promote an industry, sometimes by taking a more friendly approach to regulation.

A winding down

But, as Rhines said, the notion that such dealmaking will or can continue unabated is far-fetched.

Interest rates are, as he said, “unrealistically low” – they will have to rise at some stage. When they do, leading companies will review balance sheets, enthusiasm for M&A and reduce any growth in liabilities.

Similarly Rhines observed that “too many acquisitions drives up the price of acquirees”. At some point those tags will reach their own peak.

Regulators may meanwhile choose to intervene on anti-trust grounds if consolidation goes too far. Take your pick from the European Commission, Federal Trade Commission and quite a few others.

This is a ‘unique’ year, Rhines said….But where does it leave the engineer.

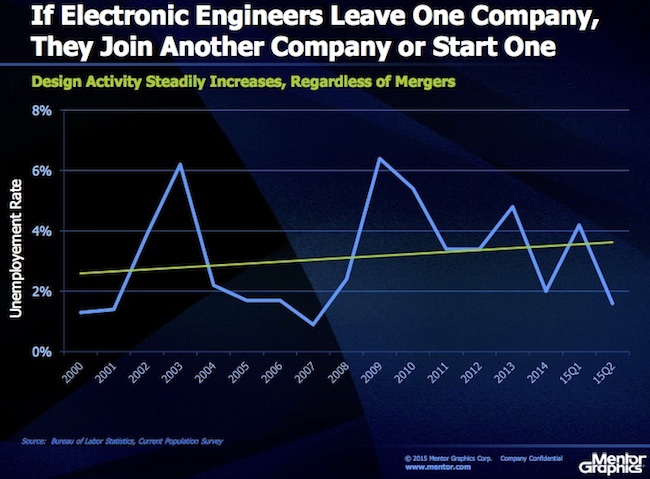

The reality, he showed, is that while M&A is happening at breakneck pace and managements are often proclaiming savings all over, the engineer faces fewer threats.

People who leave (or are forced out of) one company soon find a new home or set up their own businesses. In the second quarter of 2015, the US unemployment rate for engineers dropped below 2%.

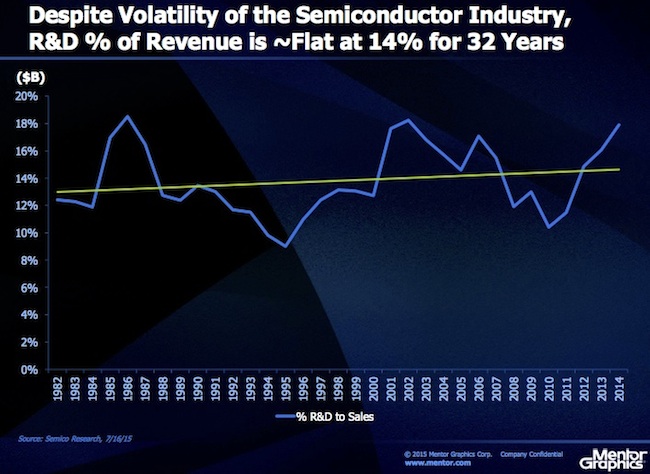

M&A waves also appear to have relatively little effect in isolation on semiconductor R&D spending. That has conformed to a flat trend line of about 14% of revenue for more than three decades.

Amid the merger mania, those are some welcome signs of stability.