Conference demonstrator brings printed-electronics suppliers together

Printed electronics has hit that chasm-crossing point. Some applications have developed into sizeable businesses but for the technology to go mainstream it needs to overcome the problems of getting it into the hands of end-user companies who don’t have the resources to integrate all the necessary components.

A repeated complaint made at this year’s Printed Electronics Europe conference in Berlin, Germany was a lack of integrators able to bring together the many different processes available into something usable. But suppliers in the field are beginning to work with each other to try to bridge the gap.

Raghu Das, CEO of conference organiser IDTechEx, claimed in his opening speech at the event that the technology is reaching its tipping point. “We have found more companies than ever who are working on printed electronics. They are end users mostly but they have people dedicated to printed electronics. They are funding custom prototypes and even looking at pilot trials.”

The issue is the type of user involved. “It’s really the marketing people who have the major need to move the technology out and scale it up, but they need to show that the product is needed and saleable. They find that printed can add value as they face increasing friction from private-label brands – their work is very creative because these companies are looking for differentiation,” says Das.

Integration needs

The problem is that the end-user companies do not want to build their own assembly lines to do what may be limited short-run projects. Tony Offley-Shore, senior electronics designer at toymaker Hasbro, says the value of an individual product line for the company is generally only single-digit millions of dollars.

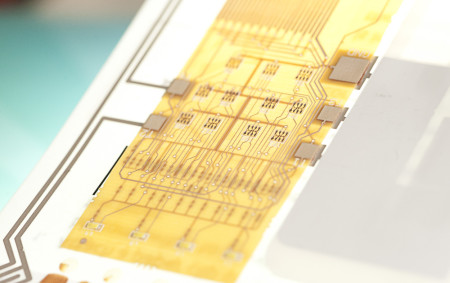

Image Printed transistors and battery (right) on the IDTechEx timer demonstrator

Segments of the market that have taken off have demonstrated the importance of an ability to ship near-finished product. Over more than a decade, Clothing+ has become the main supplier of conductive textiles for sportswear manufacturers, such as Adidas and Garmin. Clothing+ supplies the heart-rate monitor straps they sell with their watches and is now beginning to provide similar systems for women’s sports bras. However, Clothing+ has the unusual position of being able to provide most of its own technology for conductive textiles although the company is now looking to find partners so the company can incorporate more printed technology, according to CEO Akesli Reho.

To try to keep projects on track, a number of the component and materials suppliers have taken on the role of integrator. Conductive-ink specialist T-Ink has forged deals with technology developers to get some products onto the market. In other cases, the integration has been more informal.

Matt Ream, vice president of marketing at printed battery company Blue Spark Technologies, says: “In some cases we’ve had to take on the integration role or act as the quarterback on a project.”

Timer demonstration

Blue Spark was one of the companies involved in a project for the conference intended to show how collaboration could work. IDTechEx asked a variety of companies to come together to build a demonstration product given away to delegates.

Stan Farnsworth, vice president of ink supplier Novacentrix, says: “Startups have been working on their technology niches, but our customers need all of this to come together into something. So we formed this informal consortium.”

To help develop the demonstrator, the team enlisted the help of engineers from an end user – Procter & Gamble.

“P&G provided a set of requirements. We learned how to work with each other. And we had an actual end user to work with,” says Farnsworth.

Ream adds: “The aim was to create something with an eye to commercialisation. We didn’t want to just do a technological demonstrator. We wanted end-user input. If we were to put printed electronics onto something [P&G] might want to manufacture what would that look like?”

“Their input was very useful,” Das says.”Initially we thought we would do a simple, single-user timer that could count to 30. P&G said anyone can count to 30 in their head, they wanted something more sophisticated.”

The result was a timer that could be controlled by folding over different corners of the paper substrate. Activating and resetting the timer is handled by a simple paper clip to complete the circuit.

Ream says to get the project underway “IDTechEx sent the word out to see who would participate and see what technologies would be available”.

“The discussion was over many months, but it was in the last three or four months that the team really came together,” says Farnsworth. “It shows that there is a responsiveness in the industry. These are technologies that are essentially off the shelf at this point but we can integrate them to get an optimal fit. Everything we did was with an eye towards performance and towards price.”

Hybrid design

It was not the first time that IDTechEx has tried this approach but it is arguably the most highly integrated form of printed electronics that the conference team has had put together so far.

Last year’s project, a paper mat that measured the temperature of a drinks cup placed on top of it, used a silicon IC to perform its logic functions, although most the rest of the design used printed technology. This year’s design implemented the logic using printed transistors, although there wasn’t time to incorporate a printed display based on OLED or electrochromic technology.

“Ideally, we hoped this would be fully printed but there wasn’t time to an electrochromic display so we used LEDs instead,” says Ream. “This is an approach we often take: we do a lot of hybrid electronics.”

Chip LEDs were mounted on the same flexible substrate as that used for the transistors. However, many of the companies working in the field now regard hybrid implementations using both printed and silicon elements as being inevitable. It will take time for volumes to develop far enough to displace what are today extremely low-cost components.

It’s not just the silicon. A basic lithium coin cell costs a couple of cents. The cheapest printed batteries are an order of magnitude more expensive right now because they are not in applications that can push their products into the massively high volume domain of the coin cell. A printed battery has the advantage of being flexible, easy to shape and not so prone to catching fire – Blue Spark, for example, uses a carbon-zinc chemistry.

The flat, flexible battery powers a 200-transistor logic circuit made by Pragmatic Printing at the UK’s Centre for Process Innovation (CPI), which has a production line for additive manufacturing.

Printed logic

“With the printed logic, Pragmatic provided the brains for the device and probably had the hardest task. It was an off the shelf design for the battery itself. We had used it for another project that we had done with Pragmatic,” says Ream. “We picked it because it was already there and have worked with the Pragmatic technology. It met their voltage and current requirements.

“CalPoly came up with the look and feel and had the job of the graphics and circuit design,” Ream adds.

Joao de Oliviera, vice president of business development at Pragmatic, says: “The timing accuracy is not great because we have not implemented voltage regulation of the battery. The transistors are also sensitive to light, which will also affect timing.”

The sheet of polymer carrying the electronics is glued to the paper substrate. Ream says: “The connections we used for this are not those we would use for a high-volume product. The electronics will probably last longer than the timer itself. This design is between a prototype and final production. We are looking at version two of this, which will be a little more optimized.”

Ream says one possibility is to do a modular version that makes it possible to incorporate sensors and other printed elements.