Capacity shortages loom if 2017 growth repeats

The surge in semiconductor sales during 2017 has led to a split in sentiment for 2018 among analysts tracking the sector. But if current trends persist, shortages in wafers are likely to follow, hurting the ability of some companies to ship silicon and boost the prices for those who can.

A number, such as Gartner and IC Insights and the industry’s own WSTS, are looking to a return to single-digit growth for this year although most have upgraded their forecasts during 2017 and into 2018. IC Insights has predicted high single-digit growth even amid healthy expected growth in the world economy, which now has a strong pull on overall shipment levels. Organizations such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have upgraded global growth forecasts for 2018 for most regions, including Europe and Japan.

Future Horizons has taken a more bullish approach, forecasting double-digit growth driven largely by increases in pricing as shortages bite in the face of restricted capacity growth: a possible replay of the mid-1990s.

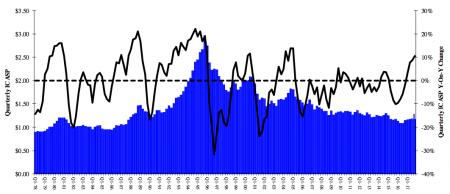

Image Average selling price growth has hit levels not seen for more than a decade (Source: Future Horizons)

Malcolm Penn, president of Future Horizons, said at the company’s London winter forecast seminar the market is displaying the characteristics of one suffering from shortages: “People are now talking about three-year contracts. It’s a completely different situation to where they were talking about three-week deals and coming back to negotiate the price down.

“It won’t change the psyche of the industry. When there is finally an oversupply they will be back to those three-week contracts again.”

Although shortages are nowhere near as publicly obvious as in prior chip booms, Penn said there are sectors where IC suppliers have had to put customers on allocation as they attempt to ration product. “The supply chain is not as broad. These things are not as public as they used to be.”

Last year, catalog distributors reported strong sales and said there had been increased buying from customers who would normally order from high-volume suppliers as customers tried to juggle product availability. In October 2017, Mouser Electronics vice president of marketing Graham Maggs said: “We do not promote volume sales but in the last year where people are looking for inventory customers have looked for larger quantities. With OEMs and EMS providers, when they come to us, it’s an indication that there are shortages in the market.”

Although the prospects for sales remain good, equipment purchases have been pulled back amid scepticism that the 2017 surge is sustainable from an industry used to lackluster growth since the 2008 financial crisis. Samsung, now the biggest buyer of chipmaking equipment driven largely by the push towards 3D NAND flash is expected to curtail spending this year, Penn said. Thanks to the rise of 3D NAND and poor initial yields, sales of etching equipment surged 80 per cent in 2017 and outpaced in dollar value those for lithographic scanners.

“People are saying, no matter how good [2017] was, this year will be horrible,” Penn added. “No-one wants to take a risk and put their head above the parapet and say it’s going to be a good growth year.”

The problem, Penn argued, is that if sales do ramp up as Future Horizons expects, manufacturers will be unable to meet demand for more than a year – risking the overheating of the overall market. “The supply chain can’t react in less than a year.”

Because of likely shortage-driven price rises, Future Horizons expects growth for 2018 to be more than 20 per cent in the most likely scenario and that it would take the global economy suffering a misstep for this not to occur. That would take global semiconductor sales towards $500bn.