Engineering creativity

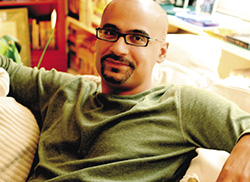

To the world at large, Junot Diaz is well on the way to becoming a literary superstar. His novel The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao has already earned critical superlatives and the 2008 Pulitzer Prize for Literature. And deservedly so. It is a fabulous, accessible book, expressed in language that—when you buy a copy (and, trust me, you will)—immediately exposes the poverty of my attempts to praise it here. However, Oscar is not the main reason for our interest.

Like most authors—even the most successful ones—Diaz has ‘the day job’, and in this case it is as the Rudge and Nancy Allen Professor of Creative Writing at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Yes, he spends a large part of his time teaching scientists and engineers who are, in his words “only visiting the humanities.”

The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao and Junot Diaz’s earlier collection of short stories, Drown, are both published in the USA by Riverhead Books.

What Diaz is trying to achieve goes beyond the ‘challenge’ traditionally associated with science students and the written word. There is a lot of talk today about turning engineers into bloggers, smoothing communication within multi-national teams, and the profession’s need to explain itself to the outside world. Diaz aims to stimulate their creativity.

While that might sound less practical, when I mentioned this interview to a senior Silicon Valley executive, his eyes lit up. In his view, the one thing that university courses often fail to address is students’ more imaginative capabilities. The industry does need team players and ascetically analytical thinkers, but given the obstacles it faces today, it desperately requires more newcomers who can make innovative leaps and deliver original ideas.

Diaz, for his part, does not approach his engineering majors from the perspective that they are all that much different from those focused on the humanities. At heart, it is about potential and engagement, not stereotypes.

“Yes, they’re brilliant and yes, they’ve sacrificed a lot of social time to their studies, and yes, they’re intense. But at the arts level, they seem a lot like my other students,” he says. “I think there’s a tendency at a place like MIT to focus on what’s weird about the kids, but really what amazes me is how alike they are to their non-science peers. Some are moved deeply by the arts and wish to exercise their passion for it; many are not.”

At the same time, he has noticed that science must, by its nature, place some emphasis on a very factual, very dry discourse and a hardcore empiricism. That is not a bad thing, rather the reflection of the demands of a different discipline.

“But it is in a class like mine where students are taught that often the story is the digression or the thing not said—that real stories are not about Occam’s Razor but something far more beautiful, messy, and I would argue, elegant,” he says.

There is another side to this dialogue—what the students bring to the classes as well. On one level, there is an inherently international side to MIT, given its reputation as a global center of excellence.

“I get to read stories from all over the world. What a wonderful job to have, to be given all these limited wonderful glimpses of our planet,” says Diaz. “Having a student from Japan use her own background to provide constructive criticism about describing family pressures to a young person from Pakistan is something to cherish.”

Multi-culturalism is something that strikes a chord with Diaz for personal reasons. He is himself an immigrant from the Dominican Republic, and his experiences as part of that diaspora, that country’s often bloody national history and his own youth in New Jersey all deeply inform Oscar Wao and his short stories.

“Many of my students are immigrants, so I know some of the silences that they are wrestling with,” Diaz says. “It makes me sympathetic but also willing to challenge them to confront some of the stuff that we often would rather look away from: the agonies of assimilation, the virulence of some of our internalized racial myths, and things like that.”

However, those students with a science background also inspire him. “In every class, I see at least one student who thinks the arts are ridiculous frippery, become, by the end of term, a fierce believer in the power of the arts to describe and explode our realities as human beings,” says Diaz.

“Why I love non-arts majors is that they are much more willing to question the received wisdom of, say, creative writing, and that has opened up entirely new lines of inquiry. My MIT students want you to give them two, maybe three different definitions for character. And that’s cool.”

Diaz’s own taste in authors puts something else in the mix here. The fantasies of Tolkien prove a frequent touchstone in his novel, although he seems even closer to a group of other English science-fiction writers who—arguably taking their cue from the genre’s father H.G. Wells—explore nakedly apocalyptic themes, especially John Christopher. His prescience is indeed seeing him ‘rediscovered’ right now in the UK, for works such as The Death of Grass (a.k.a. No Blade of Grass), which foresees an ecological catastrophe.

“Christopher had a stripped-down economic style and often his stories were dominated by anti-heroes—in other words, ordinary human beings,” says Diaz. “He may not be well known, but that changes my opinion not a jot. Like [John] Wyndham, like [J.G.] Ballard, Christopher deploys the apocalyptic mode to critique both our civilization and our deeper hidden selves, but I don’t think anyone comes close to his fearless, ferocious vision of human weakness and of the terrible world we inhabit.”

With opinions like that, MIT is obviously an excellent place to stir up the debate.

“I often find myself defending fantasy to students who themselves have to defend science-fiction to some of their other instructors,” says Diaz. “That’s why we’re in class, to explode these genres, to explore what makes up their power and why some people are immune to their charms.”

So, it is a pleasure rather than a challenge for this author to bring arts and literature to those following what we are often led to believe is a very separate academic and intellectual path. In fact, his parting thought is that the combination may in some respects be an improvement, more well-rounded even.

“All I can say is this one thing about engineering and science students: they are so much more accustomed to working as a team, and that’s a pleasant relief from the often unbearable solipsistic individualism of more humanities-oriented student bodies,” says Diaz.